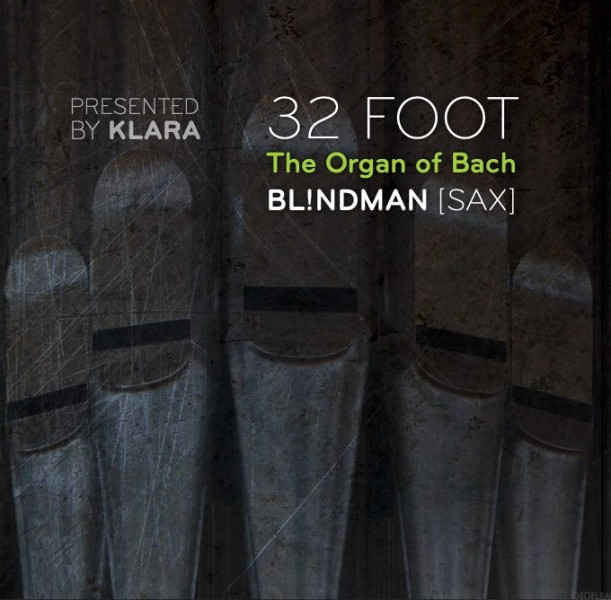

32 FOOT

The saxophones of BL!NDMAN play the monumental organ music of J.S. Bach. In Bach’s time the organ had taken on the orchestral proportions that were fully used by the composer.

By dividing the parts, the brilliance of the compositions appears all the more clearly on the surface. By doubling with the tubax and electronics, the low sounds, so typical for the 32 foot pipes of the large organs, are generated. BL!NDMAN [sax] thus becomes a human organ, moved by breath.

The CD 32 FOOT / The Organ of Bach was awarded the KLARA for best CD recording in 2014.

Eric Sleichim: artistic direction, arrangements, tubax and electronics

BL!NDMAN [sax]

Pieter Pellens: soprano saxophone

Hendrik Pellens: soprano and alto saxophone

Piet Rebel: tenor saxophone

Sebastiaan Cooman: baritone saxophone

32 FOOT / the Organ of Bach is a BL!NDMAN-production commissioned and coproduced by Festival Oude Muziek – Utrecht and deSingel and in cooperation with KLARAfestival and Flagey.

Programme

Johann Sebastian Bach / Arr. Eric Sleichim:

BWV 598: Pedal-exercitium in G minor

BWV 582: Passacaglia & Fuga in C minor

Organ Chorale: Meine Seele

BWV 583: Trio in D minor

BWV 564: Toccata in C Major

Franco Donatoni: Rasch

or

Frederik Neyrinck: B.S. unfolded …

Johann Sebastian Bach / Arr. Eric Sleichim:

BWV 535: Prelude & Fugue in G minor

BWV 596: Concerto in D minor nach Vivaldi

Agenda

Contemporary echoes of a musical past

BL!NDMAN’s approach to early music using modern instrumentation seeks to achieve a reformative transformation, rather than an exact imitation. For the past 20 years, BL!NDMAN has been constantly engaged in the search for a saxophone sound that throws new light on old music. Central to this is timbre, as is the way in which the tone can be consciously influenced by the whole body, even the voice box.

In Bach’s time, the organ was like a huge synthesizer; the ‘King of instruments’ with its myriad hues and possibilities. In order to play polyphonous music, the organist, by changing manuals, has access to a range of registers through which the tissue of voices can be followed perfectly.The quartet can achieve this differentiation by utilising the very specific spectrums of each saxophone – soprano, alto, tenor and baritone.

When arranging organ works, you are constantly confronted with melodies whose high or low notes are beyond the reach of one of the individual saxes. Exciting call and response playing then comes into play, where motifs and melodies are passed on almost unnoticed, like in a musical relay. The instrumentation closely follows the structure of the music, like the play of themes, counter-themes and spill-over passages in the fugues, or the variation technique in the Passacaglia.

When I went through Bach’s organ oeuvre, it struck me that he rarely spells out a specific register or tone. It is only in a single score that Bach explicitly mentions the extremely low 32 ft register: that of Vivaldi’s Concerto in D minor, which he rewrote for organ. This is a magnificent piece, in which the majestic riches of the organ are united with Vivaldi’s lively instrumental virtuosity. Here, the pedal passages, intended for the longest organ pipes or bass pipes, the 16 and 32 footers, are played on a tubax (a new 21st century instrument, like a kind of double bass sax). The opening work, Pedal-exercitium BWV 598, is a fragmentarily preserved solo of 33 bars, intended to improve the trainee organist’s pedal work. As well as his ten fingers, which can operate three or four keyboards on the organ, an organist also uses both feet.

Whilst technique is the main point of this pedal study, the famous Passacaglia in c BWV 582 already belongs to the category of ‘art that conceals art’. Indeed, at the beginning, we hear the pedal very clearly, in a simple melody of eight bars, but in the fanned-out continuation, Bach goes to great lengths to conceal that it is just these few simple notes that make up the foundations on which the whole powerfully-constructed building work rests. This Passacaglia shows Bach at the very height of his variational powers. Bach’s organ work contains an inexhaustible wealth of genres, forms and styles, even within one and the same composition. Toccata, adagio, fugue BWV 564 is a striking example of this.

In Bach’s hands, the Toccata – once begun in Venice as a sort of free improvisation to loosen up the fingers and to impress the listener with rapidly played passages – mushroomed into a monumental, sometimes multi-part work that he would frequently round off with a fugue. This Toccata can be divided into three parts. Only the rhapsodic beginning is a real toccata, to which Bach has added an Adagio and a Fugue.

Naturally, the organ is closely linked to church music. But Bach made certain forms of secular music accessible to organists. The new Italian music, particularly the music of Vivaldi, inspired him to do this. The Concerto in D minor BWV 596 is a work for organ solo that he modelled on the example of Vivaldi’s violin concertos. The five-part work has two very short, slow interruptions – a three bar Grave and a twenty-three bar Largo. The substantial parts are mainly the middle part (a fugue) and the finale. It is probably no coincidence that he chose, amongst others, a concerto with a fugue (rather unusual with Vivaldi).

The Triosonata BWV 583, a beautiful adagio, also has a secular character; a ‘sonata da camera’ in which two soloists are accompanied by the basso continuo (here the baritone saxophone). A combination of Italian melodiousness and solid counterpoint.

The striking thing about the Preludium BWV 546 is the recurring, solemn ritournelle, alternated with fugal triplets, whilst the Preludium and Fugue BWV 535, a later revised work from his youth, shows clear traces of a tradition inherited from Buxtehude. However, a fugue does not always need to come across as a strict mathematical form. An example of this is the BWV 578, one of Bach’s earliest large-scale organ fugues, also known as the ‘Little Fugue’, which has already been subject to multiple arrangements.

Eric Sleichim, July 2013